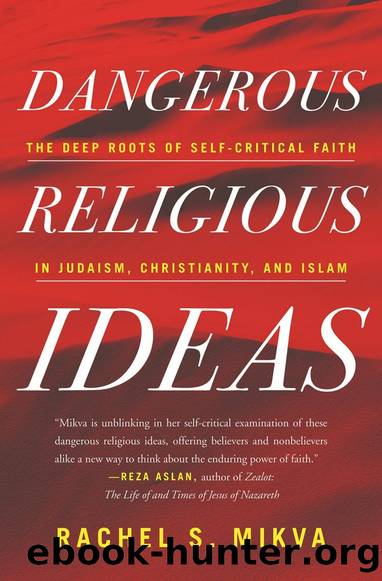

Dangerous Religious Ideas: The Deep Roots of Self-Critical Faith in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam by Rachel S. Mikva

Author:Rachel S. Mikva [Mikva, Rachel S.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9780807051870

Amazon: 0807014761

Barnesnoble: 0807014761

Goodreads: 51457969

Publisher: Beacon Press

Published: 2020-12-15T00:00:00+00:00

THE SHAPING OF EMPIRE AND OTHERNESS

It is not clear to what extent religion was the driving force of Islamâs imperial ambitions. Various records suggest the conquerors were Arabs more than Muslims. According to Jonathan Berkey, âUmar seems to have regarded himself, first and foremost, as the leader of the Arabs, and their monotheistic creed as the religious component of their new political identity.â One telling example is that he did not require Christian Arabs to pay the jizya, the head-tax theoretically imposed on all non-Muslims in the new empire.18 Yet it is worth calling to mind Walter Winkâs comment: âThe gods are not a fictive masking of the power of the human state; they are its actual spirituality.â19 Islam forged a theology that justified conquest and shaped the emerging culture at the same time that the rapid growth of empire influenced the faithâs early development. There are numerous religious themes that relate to conquest, including greater and lesser jihad, ethics of military engagement, the conceptual division of dar el Islam and dar el harb (abode of Islam and abode of war), and dhimmi status for People of the Book.20

Of these, dhimmitude seems to be most substantially linked to ideas of chosenness in Islam, but the others require at least brief attention, particularly in the current political climate that overemphasizes militant expressions of Islam. Jihad means struggle, not holy war; it designates striving to follow in the way of Allah. Islamic tradition recognizes many different kinds of jihad; while it includes military struggle, it can also connote struggle against persecution, against materialism, or for deeper commitment to Godâs will. A well-known hadith reports that Muhammad charged a group coming home from battle, âYou have returned from the lesser struggle to the greater struggle,â which is understood to mean that spiritual striving is more challenging or more religiously significant than conquest.21 Although the chain of transmission is contested, the teaching still shapes the way most Muslims think about jihad; the distinction it makes actually facilitates self-critical faith. Some argue that jihad is by definition nonviolent. Nadia Yassine (b. 1958), a spokeswoman for a prominent Islamist movement in Morocco, maintained that the sin of istikbar (arrogance) is the driving force of Islamist violence. Muslims are required to struggle against this lust for power: âA true mujahid will never deploy violent instruments or engage in practices that themselves express the urge to dominate others.â22 Education, protest, and peaceful political activism are their tools for societal transformation.

Islamâs instructions for the conduct of war require a capacity of self-restraint. Qurâan 2:190 authorizes the community to fight against those who fight against them, but without transgressing limits. Although contemporary extremists lead many people to presume otherwise, Islamic law forbids harm of noncombatants, mutilation, and other excesses of battle.23 Todayâs Islamophobia industry contributes to the erroneous assumption that Muslims divide the world into the abode of Islam and the abode of war, a binary perspective that conjures images of global conquest. The medieval terminology merely sought to establish

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Getting It, Then Getting Along by L. Reynolds Andiric(655)

Religion and Politics Beyond the Culture Wars : New Directions in a Divided America by Darren Dochuk(575)

Global Justice, Christology and Christian Ethics by Lisa Sowle Cahill(429)

Positive Psychology in Christian Perspective: Foundations, Concepts, and Applications by Charles Hackney(355)

Forgiveness and Christian Ethics by Unknown(349)

Douglas Hamp The First Six Days by Unknown(296)

The Horrors and Absurdities of Religion by Arthur Schopenhauer(271)

Insurgency, Counter-insurgency and Policing in Centre-West Mexico, 1926-1929 by Mark Lawrence(266)

Middle Eastern Minorities: The Impact of the Arab Spring by Ibrahim Zabad(250)

Christian Martyrdom and Christian Violence by Matthew D. Lundberg;(242)

Beyond Heaven and Earth by Gabriel Levy(236)

The Oxford Handbook of Greek and Roman Mythography by R. Scott Smith;Stephen M. Trzaskoma;(235)

God and Eros by Patterson Colin;Sweeney Conor;(230)

The Bloomsbury Reader in Christian-Muslim Relations, 600-1500 by David Thomas;(223)

Autobiography, Volume 2: 1937-1960, Exile's Odyssey by Mircea Eliade(216)

Witches: the history of a persecution by Nigel Cawthorne(211)

Cult Trip by Anke Richter(210)

An Introduction to Kierkegaard by Peter Vardy(202)

The Global Repositioning of Japanese Religions by Ugo Dessi(196)